About Child Sex Trafficking

Child Sex Trafficking is a severe form of child sexual abuse that is illegal in all 50 states. According to the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, the sex trafficking of minors is the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, obtaining, patronizing, or solicitation of a person under the age of 18 for the purposes of a commercial sex act, defined as any sex act for which anything of value is given to or received by any person. In simple terms, it is the exchanging of something of value for sex with a child/minor. While proof of force, fraud, or coercion is required for adult sex trafficking victims, these elements are NOT required when the victim is a minor, nor is it a requirement that a 3rd party benefit from or facilitate the exchange. That is, the youth does not have to have an identified trafficker to be a victim of trafficking. (“Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children—CSEC” is a commonly used related term.)

Examples of Child Sex Trafficking

- A 14-year old meets a “friend” online and engages in a relationship with him. The “friend” wants her to have sex with his friends in order for him to get money to pay his rent.

- A mother allows her drug dealer to engage in sex acts with her 6-year-old son in exchange for drugs.

- A 15-year-old girl exchanges sex for free rides from a ride share driver.

- A 16-year-old transgender youth has sex with a physician in exchange for hormones and money for medical procedures needed to achieve a physical body consistent with their gender identity.

- Boys, as young as 12, on a reservation are recruited by a tribal member to sell drugs and engage in sex acts with casino visitors for which the boys are provided cash, phones, and clothes.

- An 11-year-old boy is sent a cell phone from someone he meets on his gaming system in exchange for the boy masturbating live on camera.

- A 15-year-old Guatemalan girl is sent to live in the U.S. with her uncle, who promises her a better life. The uncle forces her to engage in sex acts with his business associates for money.

- A 13-year-old girl runs away from her group home with a 14-year-old peer. The friend takes pictures of her and places an ad for sexual services on an adult services website to get money to cover the cost of their hotel room and food.

Child Labor Trafficking similarly involves the exploitation of children for monetary gain and often co-occurs with Sex Trafficking. We know that there is intersectionality of child labor trafficking and child sex trafficking. Currently, these webpages will only focus on Child Sex Trafficking. |

Child Sexual Abuse Materials and Imagery (formerly called, ‘child pornography’) is a specific form of sexual exploitation that involves any visual depiction of sexually explicit conduct involving a minor. For more information click here. |

Who is Most Vulnerable?

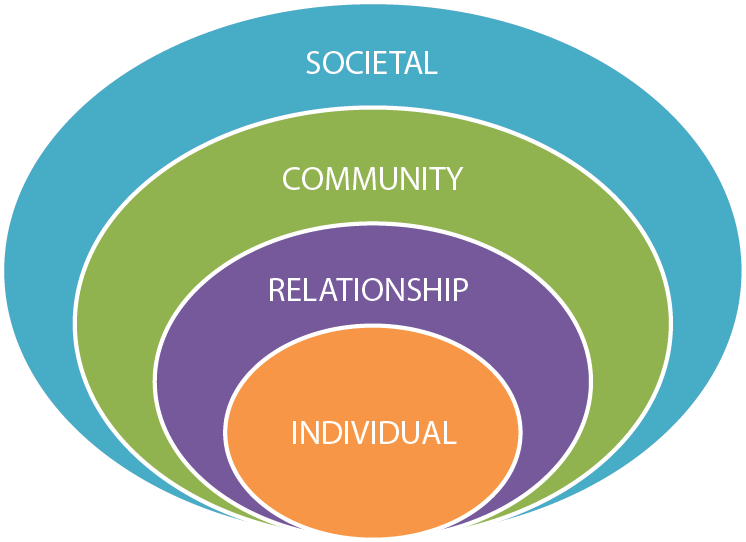

Sex trafficking occurs among all socioeconomic classes, races, ethnicities, and gender identities in urban, suburban, rural communities, and on land-based nations and other tribal communities across the U.S. However, some youth are at heightened risk due to a complex interplay of individual, relationship, community, and societal factors. Click here for more information.

Societal: Sexualization of children, gender-based violence, strict gender roles, homophobia and transphobia, tolerance of the marginalization of others, lack of awareness of child trafficking, lack of resources for exploited youth, social injustice, structural racism, and tolerance of community and relationship violence.

Societal: Sexualization of children, gender-based violence, strict gender roles, homophobia and transphobia, tolerance of the marginalization of others, lack of awareness of child trafficking, lack of resources for exploited youth, social injustice, structural racism, and tolerance of community and relationship violence.- Community: Under-resourced schools and neighborhoods, community violence, community social norms, gang presence, commercial sex in the area, transient male populations in the area, poverty and lack of employment opportunities.

- Relationship: Friends/family involved in commercial sex, family dysfunction, intimate partner violence, caregiver loss or separation, lack of awareness of child trafficking, poverty, and unemployment.

- Individual: Abuse/neglect, systems involvement youth (child protection, juvenile justice), homeless/runaway, LGBTQ identity, intellectual and/or developmental disability, truancy, unmonitored/risky internet and social media use, behavioral or mental health concerns, substance use, unaccompanied migration status.

Familial Trafficking

Familial trafficking involves the intentional or unwitting exploitation of children/youth by individuals who are responsible for the care, safety and trust that is foundational to how society understands and defines the family. Some ways that family members initiate child sex trafficking include:

- Caregivers engaging with traffickers who fraudulently promise to obtain jobs or other opportunities for their children, and instead force the children into commercial sex, strip club involvement, production of child sexual abuse materials (formerly called, ‘child pornography’), etc.

- Caregivers providing inadequate supervision leaving children/youth vulnerable to those who sexually exploit them.

- Family members not otherwise engaged in trafficking allowing traffickers to exploit their children/youth in exchange for drugs, money, or something else of value.

- Family members exploiting/trafficking their own children and potentially others.

Methods used to control or sustain involvement of youth in family sex trafficking include psychological, physical, and/or sexual abuse. Studies demonstrate significant psychological and physical harm, and high levels of clinical need in these sometimes younger, child victims, including high rates of PTSD (80%), psychiatric hospitalization (35%) and suicide attempts (48%). This strongly underscores the need to specifically focus counter-trafficking prevention and intervention services to families with children/youth.

Young children are often under identified. They may be especially vulnerable to familial trafficking and may not be aware that something has been exchanged. In many cases the abuse is normalized, with multiple generations and family mem- bers directly involved or complicit. Professionals who work with young children should look beyond conventional views of sexual abuse. They also should consider the possibility the caregiver has received something of value in exchange for access to the child, essentially child sex trafficking.

*International Organization for Migration. (2017). Counter-Trafficking Data Brief: Family Members are Involved in Nearly Half of Child Trafficking Cases. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

*Sprang, G., Cole, J. (2018). Familial Sex Trafficking of Minors: Trafficking Conditions, Clinical Presentation, and System Involvement. Journal of Family Violence, 33, 185–195.

Immigrant and Refugee Youth

Immigrant and refugee children are vulnerable to sex trafficking, especially when they are unaccompanied by a parent or guardian. Factors prompting migration may elevate the risk of sexual exploitation, including violence in the community or within the home, armed conflict and prominent gang activity in the area. During transit, economic deprivation, breakdown of family and social structures, imbalance in power relations and dependence on traffickers and/or smugglers to cross borders render children at risk for exploitation. Unknown physical surroundings, fear of law enforcement, social isolation, and food insecurity com- pound the risk. In the destination country, additional factors contribute to increased vulnerability to trafficking and exploitation including the social and physical structure of refugee camps and other housing situations (e.g., over-crowding, deprivation, inadequate supervision). Limited knowledge of legal rights within the new country, distrust of authorities, and language barriers only add to the vulnerability.

LGBTQ+ Youth

Youth who identify as LGBTQ+ are disproportionately impacted by a wide variety of traumatic experiences including abuse and neglect, harassment, and family rejection, all of which place them at risk for trafficking. LGBTQ+ youth who lack family support or safe shelter are vulnerable to traffickers who are seeking to exploit their needs for housing, food, and social connections.

LGBTQ+ youth are at disproportionalte risk for sex trafficking and sexual exploitation. In fact, even among runaway/homeless youth, LGBTQ+ youth experience commercial sexual exploitation at greater rates than their heterosexual cisgender counterparts.*

Youth facing housing and employment discrimination related to their actual or perceived gender identity or sexual orientation may feel they have no choice but to exchange sex acts for items and conditions necessary for survival like shelter or food. This is sometimes refer to as “survival sex.” Furthermore, the lack of LGBTQ+ affirming and inclusive schools, healthcare, legal and criminal justice systems, and other critical social services increase isolation and create barriers for youth to access support.

*Covenant House (2016). Labor and Sex Trafficking Among Homeless Youth: A Ten-City Executive Summary. New Orleans, Louisiana: Loyola University.

Poverty and Economic Factors

Economic factors and poverty appear to be important elements of trafficking vulnerability. Economic factors constrain opportunities, undermine educational attainment, impact community values and norms, and otherwise profoundly contribute to trafficking victimization. Individuals with limited opportunities to meet basic needs and/or expectations to provide monetarily for their loved ones (e.g., runaway/homeless youth, youth with impaired parents, siblings in need, young children) are especially at risk. Similarly, parents facing severe financial distress may be vulnerable to manipula- tion by traffickers and allow their children to enter into high-risk situations, or may be even more fully complicit in the sex trafficking of their child in an effort to help the family survive.

System-Involved Youth

Children and adolescents who have experienced sex trafficking often have very high rates of involvement in multiple child-serving systems, especially child welfare (e.g., Child Protective Services, foster care) and juvenile justice. The trafficking risk associated with child welfare involvement is sometimes related to the traumatic experiences (child sexual abuse, child physical abuse, neglect) that may have precipitated a child’s or adolescent’s entry into the system. Often it is related to, and compounded by, experiences that occur because of their involvement in child welfare, such as housing instability, foster care placement, disruptions in education, and continued experiences of maltreatment. Foster care in particular, especially multiple placements and earlier placement in congregate care vs. single family homes, appears to increase trafficking risk.* While, initial placement is often a result of early experiences of abuse and neglect that contribute to trafficking vulnerability, there also appears to be experiences while in care that potentially exacerbate vulnerability, including degrading of a youth’s self-worth, erosion of their belief or expectation that others will care for them, and the monetization of their care. Perpetrators, both traffickers and buyers, will often target children who are not getting their basic needs met (including those for love and belonging) because they assume they will be easier to manipulate and control.

Justice systems were once the primary systems that served youth with histories of being trafficked because youth would be arrested for “prostitution.” While there are some states that still charge minors with prostitution, other states have shifted to match federal laws recognizing victims of child sex trafficking as victims of child abuse. With this recognition, the child welfare system is increasingly becoming the intended primary system to serve children and youth who have experienced child sex trafficking.

Even with this shift, youth are still vulnerable to contact with law enforcement, probation systems, and the juvenile court. This is often due to factors related to their exploitive situations (e.g., substance abuse, coercion to commit crimes, traumatic stress reactions, and homelessness) that lead to increased interaction with law enforcement and the justice system.

* Dierkhising, C. B. & Ackerman-Brimberg, M. (2020). CSE Research to Action Brief Translating Research to Policy and Practice to Support Youth Impacted by Commercial Sexual Exploitation (CSE). National Center for Youth Law: California State University, Los Angeles.

Youth of Color/Racism and Racial Disproportionality

Although people of all races and ethnicities are trafficked, racial and ethnic minority youth are identified as being trafficked at disproportionate rates compared to non-minority (White, non-Hispanic) youth. This is likely due to intersecting economic, educational, community, and societal factors and embedded racism, and structural inequality in multiple child-serving systems (e.g., juvenile justice, child welfare, and education).

In the United States, Black, Native American, Asian American and Pacific Islander youth are especially vulnerable to trafficking due to the particular histories of oppression and exploitation, including the sexualization, objectification, and fetishization of these girls. Sexual stereotypes persist in the present day with specific implications in the commercial sex market. Biases that attribute greater physical, emotional, and sexual maturation and less need for protection and support to youth of color, furthers the harm and increases their vulnerability to trafficking.

Youth who are Homeless or Leave Placement without Caregiver Permission

Youth who leave home or placement without caregiver permission, are often rejected by caregivers, forced to leave, or unwelcome in their homes. Due to this, LGBTQ+ youth who are homeless. , may be especially vulnerable to being trafficked. Youth who are homeless often experience several risk factors increasing their vulnerability for trafficking prior to and while being homeless. That is, exposure to trauma and other stressors (e.g., poverty, abuse or neglect, violence in the home or the community, conflicted or lack of social and family relationships, disrupted education, and substance abuse) are common precipitants and consequences of trafficking. These experiences may also contribute to low self-esteem, problems with trust, depression, anxiety, and other social-emotional issues that increase vulnerability to trafficking. In particular, youth experiencing homelessness or housing instability often have unmet basic needs such as food, clothing, safety, shelter, money, or access to other resources or things of value with restricted options for securing these basic needs and resources.

Youth with unstable housing or experiencing homelessness may feel they have no choice but to exchange sex acts for items and conditions necessary for survival like shelter or food. This is referred to as “survival sex.” They may not perceive their situation to be one of exploitation, but instead view it as engaging in voluntary acts that meet their needs and preserve their independence and freedom. However, under the age of 18, any exchange of sex acts for goods, is child sex trafficking. Due to youth’s needs and vulnerabilities, they may view those who seek to manipulate them as “friends,” benefactors, or intimate partners, as well as a source of help, support, or care.

It is important for professionals, caregivers, and youth alike to be educated on the increased vulnerability to trafficking for youth who are homeless or absent from placement, especially if periods of homelessness or absence from place- ment are prolonged or repetitive, in order to inform prevention, identification, and intervention.

Youth with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD)

Youth who have disabilities (e.g., physical, intellectual, developmental, or a combination) are at increased risk for expe- riencing a range of traumatic experiences including being vulnerable to trafficking. They may be especially vulnerable because of the social discrimination and stigma they face regarding their disability.

There are many reasons why youth with intellectual disabilities may be more vulnerable to being trafficked, including lack of understanding of what is and is not sexual exploitation. These disabilities may also limit a youth’s ability to assertively refuse the propositions or directions of others and to report abusive situations. An inability to assess risk and to be overly trusting and engage in relationships in which they are sexually or financially. Often, others do not see youth with Intellectual Disabilities as sexual beings, and, as a result, they are often uninformed about concepts on sexual health including consent.

Youth with disabilities may lead more isolated lives, sometimes restricted to their caregivers and service providers (e.g. physical therapist, staff at a recreational or vocational training center). Due to this isolation and restriction, they may desire autonomy, friendship, and human connection outside of their support system. This may heighten vulnerability to exploitation of all kinds and make them especially vulnerable to manipulation by a trafficker who gives the appearance of friendship or relationship. Traffickers may also seek out victims with disabilities to gain access to their public benefits such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) benefits.

Youth with disabilities may be submissive to their caregivers and comply with their caregivers’ wishes because they are dependent upon them. This dependency on others may lend itself to youth being at risk of being compliant and submissive to traffickers and their demands.

Some youth who have disabilities depend on caregivers for intimate care and bodily cleaning or have had medical procedures that involve aftercare with physical touching. As a result, youth can become desensitized to touch and/or may be unsure about what appropriate touch is and whether they have the right to object to and report unwanted touch, sexual abuse, and sexual acts.

Youth who have disabilities may have difficulties with communication and/or speech. They may be unable to speak clearly or require communication devices or interpreters to make their needs known. This may affect their ability to get help and report any abuse they are experiencing and could require them to depend on their trafficker for interpretation of their needs.

In some cases, youth may not be believed by family, friends, or even authorities when they report their abuse and exploitation. This is especially true for young people with disabilities that affect intellectual, cognitive, or communication functions or those with mental health diagnoses.

What are the Experiences of Youth Who Have Been Sex Trafficked?

Often, youth who have been sex trafficked have experienced multiple traumas and adversities in their lives. This includes various trauma and adversities prior to being trafficked that often contributed to their vulnerability, as well as their experiences while being trafficked. Even after identified as having been trafficked, youth may face many challenges. It is helpful for professionals to be aware of these experiences and their impact on youth. while not exhaustive, below is a list of common youth experiences prior to, while being, and after being trafficked. For a more comprehensive list of these experiences, click here.

Prior to being trafficked |

While being trafficked |

After being trafficked |

|

|

|

Despite these adversities, youth are resilient and can cope with difficult experiences in many ways. It is important to note that even if youth who are being or have been trafficked have any of the experiences noted above, they may not view these experiences as traumatic. For more information visit the effects of trafficking page.

Child Sex Trafficking is a complex issue. There are a lot of components and factors that interplay with one another. Its complex nature can lead to misconceptions or misinformation. Click here for a list of things you might not know about trafficking.